Johannesburg, South Africa: The recent incident involving members of the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) singing and dancing aboard a commercial flight to East London – now kuGompo City – has ignited a spirited public debate. Clad in party regalia and chanting “Hands off our CIC,” the group was enroute to support their leader, Julius Malema, who is facing a criminal legal process for allegedly discharging a firearm in public. The reactions have been predictably ambivalent. Some South Africans dismissed the episode as harmless political expression, pointing to earlier instances of singing onboard aircraft, including by the Springboks, or even a silent disco at altitude conducted with airline approval (this came from a silent disco session organised by the airline Lift in the past). Others argued that the airline should have acted decisively, invoking the law on unruly passenger behaviour.

At first glance, the comparison with prior incidents appears persuasive. We have seen celebratory singing on flights before, and aviation has accommodated creative passenger engagement when safety is not compromised. However, this debate requires a more careful, aviation-law-informed analysis -one that turns not on public sentiment or political sympathy, but on safety, security, and the legal authority vested in the Pilot-in-Command (PIC).

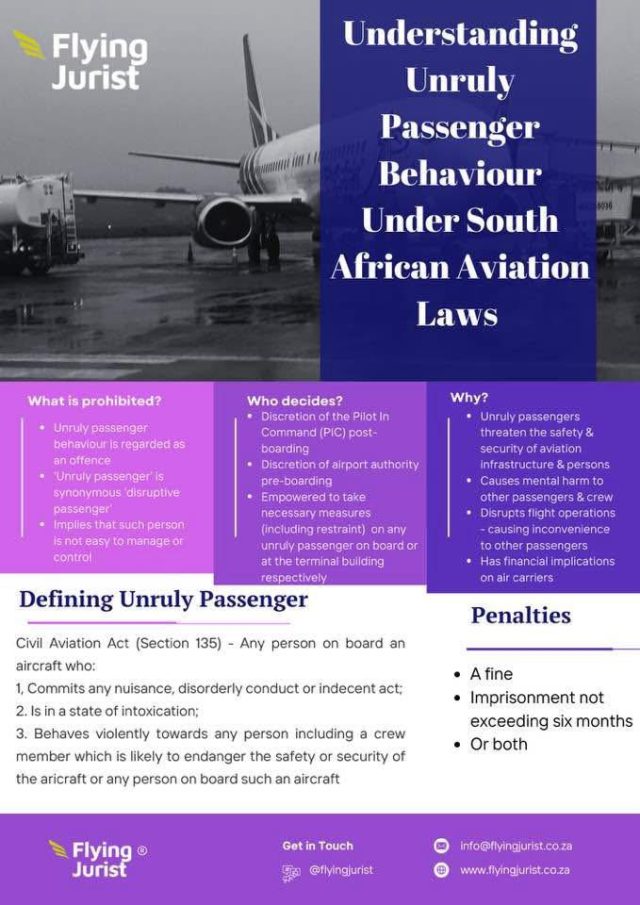

South African aviation law, consistent with ICAO standards, treats “unruly passenger behaviour” seriously. Section 135 of the Civil Aviation Act provides a framework for addressing conduct that endangers safety, disrupts order, or interferes with crew duties. Crucially, the operative word is not “singing,” “dancing,” or even “political expression.” It is unruly. And unruliness is not determined by Twitter polls or post-flight outrage; it is assessed in real time by the PIC, informed by safety and security considerations unique to the operating environment of an aircraft.

This distinction matters. A silent disco at altitude, using wireless headphones, is not unruly because it is pre-arranged with the airline, controlled, and does not impede crew movement or communication. Likewise, a national rugby team briefly breaking into song – seated, compliant, and celebratory – cannot be equated with a mass of passengers toyi-toying in the aisle, blocking movement, and generating a charged, militant atmosphere at 35,000 feet.

An aircraft cabin is not a stadium, nor is it a political rally space. It is a tightly regulated security environment. Cabin crew are not merely service providers; they are, first and foremost, safety and security officials. Their ability to move freely, access all areas of the aircraft, and communicate effectively with passengers is non-negotiable. Any conduct that obstructs aisles, renders parts of the cabin inaccessible, or drowns out safety announcements edges firmly toward unruliness – regardless of the cause being advanced.

Those defending the EFF incident often invoke equality: if others were allowed to sing, why not them? The answer lies not in who is singing, but how and under what conditions. The law does not prohibit joy, solidarity, or expression. It does, however, prohibit behaviour that compromises safety or undermines the authority of the crew. A coordinated group chanting militant slogans, moving about the cabin, and creating disorder introduces variables that aviation safety doctrine is designed to eliminate.

Another overlooked dimension is perception and escalation risk. Aviation security operates on prevention. A situation need not descend into violence to warrant intervention; the potential for escalation is enough. In a confined space with limited egress, heightened political emotions, and visible group mobilisation, the threshold for concern is necessarily lower. The PIC must consider not only what is happening, but what could happen – and act before control is lost.

It is also important to be clear: freedom of expression, while constitutionally protected, is not absolute in all contexts. Aircraft operations impose lawful and reasonable limitations in the interest of safety and security. The courts have consistently recognised this in aviation-related matters globally. Once the aircraft door closes, the PIC’s authority is paramount.

This is not an argument for heavy-handedness or selective enforcement. It is an argument for clarity. Airlines should communicate expectations clearly; passengers should understand that conduct acceptable on the ground may not be acceptable at altitude. Political affiliation should neither immunise nor incriminate. The standard must be uniform: does the behaviour interfere with safety, security, or crew duties?

In the final analysis, the controversy is less about the EFF and more about aviation governance. Singing per se is not the issue. Disorder is. And disorder is assessed not by public opinion after landing, but by the PIC in the moment, guided by law, training, and the uncompromising logic of aviation safety.

As we debate this incident, we would do well to remember a simple truth: at 35,000 feet, safety is not negotiable, and symbolism must always yield to command.

Prof Angelo Dube (Commercial Pilot) is a Professor of International Law, Acting Director of the School of Law at UNISA, and Chief Executive Officer at Flying Jurist, and founder of the Aviation Indaba. At UNISA he heads the Aviation Law Working Group, a consortium of pilots, aviators, researchers and lawyers who research in various aspects of aviation law. He writes here in his personal capacity.